Friends, Feats, and The Subtle Mentor

In January 2017, Emma Murray moved to Colorado after graduating from Brown University. Her chief reason, beyond the obvious outdoor recreation opportunity, was the hope of “meeting and cultivating relationships with women who were excited about the same [adventurous] things that excited [her].” Murray would eventually meet one of the greatest role models of all.

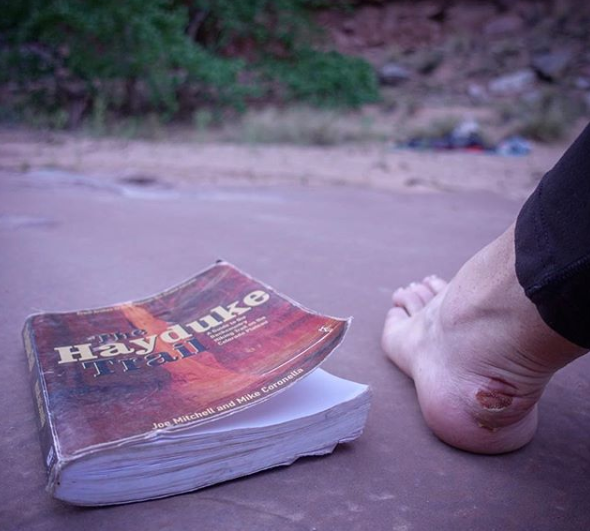

At 2:00 A.M. on April 14th, Sunny Stroeer, a record-holding endurance athlete, left the northern boundary of Arches National Park to begin the 812-mile Hayduke Trail. The backpacking route traverses the Colorado Plateau by linking numerous National Parks, Wilderness Areas, Forest Service and BLM districts from Moab to Zion National Park. Notorious for largely being an arduous and unmarked route, Stroeer not only sought a physical speed challenge, but it would also be her first thru-hike.

When Stroeer set out into the night, she had a month of trekking planned before her. Approximately 160 miles in, she made her first social media update with a photo of a quarter-sized blister on her heel. “Over the years I ran so many distances across the gnarliest terrain without blisters, so I became casual in my approach to foot care; the Hayduke is teaching me humility,” she wrote.

Murray, now a freelance journalist and editor for Boulder Weekly, had previously contacted Stroeer for an interview regarding her recent accomplishment of becoming the first woman to complete the Mount Aconcagua 360 Route in a single push.

“At the end of our interview, I asked her one of my favorite questions, which is, ‘What are your future dreams?’ And I remember so clearly; she looked at me and said, ‘Well, they’re not really dreams, they’re more to-do goals.’” Stroeer went on to describe her upcoming mission: the Hayduke. Murray, a distance runner herself, was intrigued; she is in the midst of training for her first Leadville 100 race. Stroeer promptly invited Murray to go for a run. Shortly after, Murray found herself attached to a group email with a request to the effect of, “Would love any and all company.”

“[Stroeer] outlined her day-to-day itinerary for the Hayduke trail. For the Grand Canyon section, she had put a little disclaimer that loosely said, ‘Hey this is going to be the most intense section, I would like someone to come with me.’ I discounted it, even though it was really the only part that caught my eye. [The section] also took place the weekend I had my 50-mile race scheduled,” Murray said.

Two days before the Hayduke journey began, Stroeer and Murray met once more. Stroeer expressed that no one had yet reached out to join her.

“What? That’s so lame; this seems so cool,” Murray told Stroeer, then mentioned how The Grand Canyon had piqued her interest.

“You should totally come,” Stroeer said.

“I know, but I have this race…”

“This is going to be better training for Leadville than a 50-mile race would be.”

Stroeer sent her, that night, all the permit information for The Grand Canyon and a more detailed itinerary. Then left the next day. Murray decided to commit.

When Stroeer first reported on her Instagram how blisters derailed her enough to warrant a rest day and a detour, the challenges of the trail had truly just begun. Weeks later, she wrote, “I am ~3 days slower than I had hoped to be … which has led me to shortcut some 70ish miles by bypassing Willis Creek and Bryce (an area that I already knew from logging weekend warrior miles). At this point, I am excited to start what’s commonly considered the Hayduke’s hardest section: a 150-mile east-west traverse of the Grand Canyon.”

“She skipped a section so she could meet with me,” Murray said. “I couldn’t push it back any further because of [work]. I felt really bad, though I didn’t realize it until I was driving there. But we talked about it and she was in good spirits.” Murray had also come to realize Stroeer was contending with the reality of her speed attempt no longer being a feasible goal.

“I think she was really excited about having a partner, so she felt it was worth it,” Murray said, “even though she was pretty sad she didn’t hike every single mile.”

On May 9th, after six sweltering days, Murray left Stroeer at the northwestern rim of The Grand Canyon. Stroeer had less than 200 miles left, and she swiftly reached the end of the Hayduke in Zion National Park on May 15th. She walked 685 of the 812 miles in 32 days.

“I wanted to walk across Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante while they remain wild,” Stroeer posted to Instagram, “but mostly, I just didn’t know what to expect – which is exactly why this hike was so alluring to me … The smile on my face as I descended into Zion Canyon yesterday, with hundreds of miles and an infinite amount of new memories behind me, only tells a smidgen of the story.”

The Grand Canyon Lessons

What Stroeer weaned from her thru-hike is multi-dimensional: it is a reciprocation of the land, the weather, the people she came across, the indigenous histories and presence, the solitude she encountered. All the more, Murray’s involvement created a unique generational mentorship. Murray is a decade younger than Stroeer, and though Murray had experience from solo-wandering South America, never had she carried so much weight over such distances.

“[The Grand Canyon] was pretty nuts,” Murray said. “It felt like everything was trying to kill me.” Murray, too, found herself with swollen and aching feet. A rattlesnake sat in the middle of the trail one day; while circumnavigating it, they watched it slither into the very reeds they were bushwhacking through. Yet, the inhospitable nature of The Grand Canyon epitomized this alluring dynamic for Murray as well. They both slept without a tent, near water sources, and reveled in the starlit sounds. Frogs and insects swiftly brought the desert from the boiled silence of the day into the indigo cacophony of the night.

“Between the thorny bushes, the raging sun, the tadpole infested water, the rocky, crumbly cliffs you’re walking on—I don’t know if it’s just part of our human nature to be drawn to spaces we’re not meant to be, but when you’re there, you feel so alive; you’re challenged from 360-degrees. It really brings out every element of your existence,” Murray said.

The task of hitchhiking on a raft to cross the frigid Colorado River came as another pinnacle of experience for Murray. Stroeer and Murray hiked down to the river one morning and fortunately found a group of river guides from Maine packing up camp. The ladies asked for a ferry and the guides said yes.

“Then they gave us pasta salad and pita bread, and we scarfed it down,” Murray said. “That food saved me because I ran out of snacks by the end of the trip, and if I hadn’t had that salad, which fed me for two days, I would’ve had a really bad time.”

When it came to riding in the raft, the guides had yet to navigate the Kwagunt Rapid, a class three on the international scale. Murray recalled being caught off-guard when they casually mentioned the rapid.

With fast approaching turbulence, “I asked if there was anything I needed to know. ‘Well breathe deep and yeah you should hold onto that cord right there.’ I got totally soaked and had a very cognizant, ‘breathe, breathe, it’s going to be okay.’ It was one of those things where time slowed down,” Murray said. Yet, the lessons of experience for Murray in The Grand Canyon were noticeably amplified due to the context of sharing it with someone like Stroeer.

“I learned a lot from [her],” Murray said. “She led by example the entire week, showing me her methods for navigation, route finding, camp logistics, etcetera … As we journeyed through gnarled and precarious terrain, I was able to observe how she reacted and adapted to situations big or small, urgent or germane ”

Murray believes the most fruitful mentorships are the ones with two-way paths, “where both people are invested in one another’s success.” The same can possibly be said about solo journeys and the experiences that are taken from the land or the activity itself—that sense of invested mutuality; the more you give, the more you get.

“In the Grand Canyon, I wanted to be there to support [Stroeer] through her big mission,” Murray said, “but I was also tremendously excited to learn all I could.” Stroeer echoed these sentiments of reciprocity, stating that Murray reminded her “to never say no to an opportunity, and to not let age or prior experience dictate the magnitude of your ambitions.”

Lived experiences in the outdoors, particularly ones with perceived risk, shape individuals in both nuanced and pronounced ways. These sought endeavors by athletes and outdoorists alike can be seen as an indirect form of mentorship if you will, where the unknown, or the land itself, beholds the position of teacher and guide.

Mentorship can be as subtle as a shift in perspective and as grand as an 800-mile trail through the desert; it can also be one-sided and tedious, unannounced, or unacknowledged—but I think we all seek it in our lives somehow, whether it’s through a family member or a friend, the land we hold sacred, or the way we negotiate our ambivalent selves.